The Best Clam Chowder: Spilled Milk #377

Clam chowder is the rare dish that manages to tell America's story in a single bowl: immigrant ambition, regional rivalry, the eternal war between cream and tomato. Today, I'm sharing my recipe.

Today’s FREE newsletter includes:

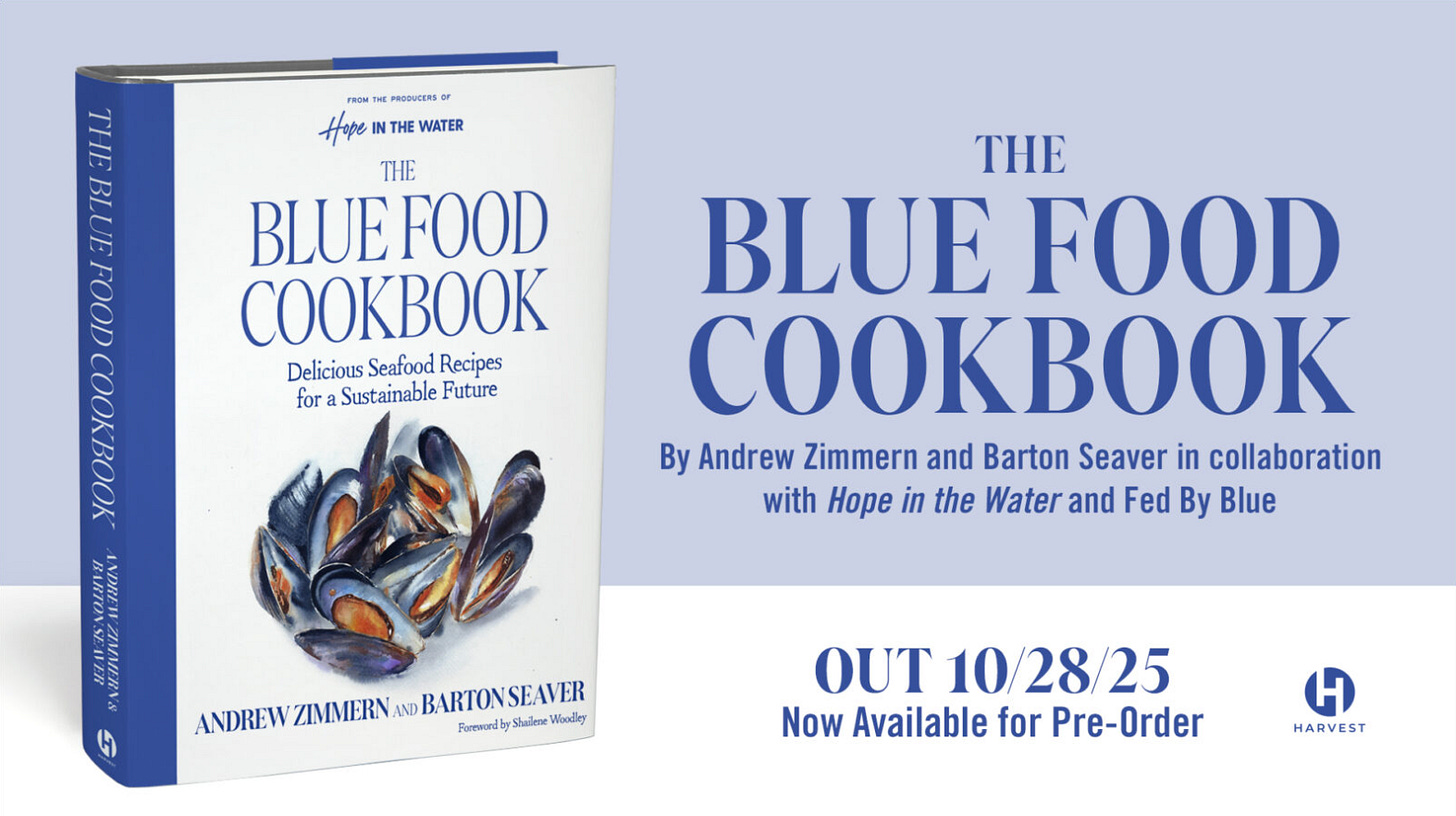

A behind-the-scenes glimpse at a recipe and some beautiful photos from “The Blue Food Cookbook,” which will be released later this month.

A close look at the evolution of clam chowder and the very real war between cream- and tomato-based versions.

A step-by-step recipe for the best clam chowder. (Spoiler alert: It’s cream-based.)

Clam chowder is one of those rare dishes that has managed to tell the story of America in a single bowl: immigrant ambition, regional rivalry and the eternal war between cream and tomato. It’s our edible history lesson, ladled hot with the brine of our coastal heritage.

The origins of chowder stretch back across the Atlantic. The word itself comes from the French chaudière, a large cauldron used by Breton fishermen who boiled seafood with salt pork and hardtack biscuits. In the 1700s, English sailors and French fishermen brought this maritime tradition to New England’s shores, where the species of the Atlantic (clams, cod, salt pork and potatoes) met colonial pragmatism. The early chowders were rustic, thickened not with flour but with crumbled ship’s biscuits and flavored with salt pork fat and onions. They were cheap, hearty and warming, perfect fuel for a region that spent half the year fighting frost and the whole year hauling nets.

By the early 19th century, clam chowder had become a fixture of Yankee cookery. Lydia Maria Child included a version in her 1832 guide, “The American Frugal Housewife,” and by 1850, you could find chowder recipes scattered through New England cookbooks like love letters to thrift and comfort. The key ingredients (hard-shell clams, salt pork, potatoes, onions and milk or cream) were all local, all affordable and all deeply tied to the region’s identity.

Great news, Spilled Milkers: “The Blue Food Cookbook,” by Andrew Zimmern and Barton Seaver, in collaboration with Fed by Blue, is available for preorder. It’s a celebration of fish and shellfish and will be your seafood bible.

Preorder it today, and it’ll be delivered to your doorstep as soon as it’s released. And in the meantime, check out the dates and locations for the upcoming book tour, and make plans to come learn about the book in person!

Then came the great schism: Manhattan clam chowder. In the early 20th century, New Yorkers, ever suspicious of anything milky and monochrome, started adding tomatoes to their chowder, reflecting the city’s Italian and Portuguese immigrant influences. It was brighter, thinner and redder than the New England version, a brash outsider in a bowl. Rhode Islanders, caught between the two, hedged their bets with a clear-broth version that pleased precisely no one outside Narragansett Bay.

The tomato base scandalized New England. In 1939, a Maine legislator introduced a bill to make the addition of tomatoes to chowder a culinary crime. It didn’t pass, but the message was clear: Tomato belonged in spaghetti sauce, not in chowder. That line in the sand, or rather, in the sandbar, cemented New England clam chowder’s cultural dominance. The creamy version became shorthand for authenticity, purity and a kind of maritime piety. Manhattan chowder, meanwhile, was forever cast as its heretical cousin, sophisticated perhaps, but slightly suspect, too cosmopolitan, too thin, too ... New York.

The real reason New England clam chowder triumphed wasn’t just regional pride; it was American nostalgia. By the mid-20th century, as mass tourism, diner culture and canned soups took over the culinary landscape, New England clam chowder became a shorthand for Yankee tradition and coastal purity. It was ladled out at Howard Johnson’s, featured on clam shack menus from Cape Cod to Key West and immortalized by Campbell’s in its 1939 canned version. Creamy chowder photographed beautifully in black and white, too; those luscious whites and grays of potato, clam and cream looked comforting and wholesome. The Manhattan version, in contrast, looked like something spilled from an overworked bolognese pot.

There’s also the matter of comfort itself. Cream-based soups speak to home and hearth; tomato-based soups speak to café tables and lunch counters. When America industrialized and urbanized, the collective appetite leaned toward the former. A bowl of New England clam chowder was a portal back to small-town America, to cold docks and family suppers people feared losing. It wasn’t just soup; it was memory management.

Today, New England clam chowder reigns supreme in our national imagination because it reconciles contradictions: it’s humble yet indulgent, simple yet layered, seaside yet suburban. Manhattan clam chowder remains the contrarian’s choice; brighter, leaner, less forgiving and arguably more reflective of modern tastes, it never stood a chance in the cultural mythology game. The cream won because it soothed.

In a country built on restless ambition, clam chowder remains one of the few dishes content to stay put. A bowl of New England clam chowder doesn’t ask for innovation; it asks for allegiance. And perhaps that’s why it endures, not just as New England’s signature dish, but as America’s enduring dream of a simpler, saltier, more honest time, when the only thing dividing us was the tone of our soup.

Recipe: The BEST Clam Chowder

Serves 6 to 8

Well, clams are one of my desert island foods, for sure. I’ve dug them out of the bays of Long Island Sound since I could walk. This soup reminds me of cold fall and early winter meals at our home out on Long Island. The fennel, chile and chives are my additions from 40 years ago. The rest is my family chowder recipe that my dad created. Grandma and Grandpa were observant Jews, so there wasn’t a lot of clam chowder at their house. I don’t keep kosher, nor did my parents. Maybe that’s why my dad loved this recipe so much — the forbidden fruit rebound effect and all that. I will tell you this: Buy a copy of “The Blue Food Cookbook” when it’s released next week, and in it, you’ll find several great recipes for fish stock, which you can use when making this chowder. Call me if you don’t find it to be your new favorite chowder recipe.

Ingredients:

4 1/2 cups fish stock

6 pounds cherrystone clams (about 48 clams)

1/3 pound salted butter (1 1/2 sticks or six 1-inch cubes)

1 fennel bulb, minced (about 1 1/2 cups)

1 serrano chile, finely minced

1 large yellow onion, diced (about 1 1/2 cups)

3 celery stalks, diced (about 1 1/2 cups)

2 carrots, thinly sliced (about 1 cup)

1 teaspoon celery seeds, toasted and crushed1

1 teaspoon fennel seeds, toasted and crushed

3 small Yukon Gold potatoes, peeled and diced (about 3 cups)

3 cups heavy cream

salt and freshly cracked black pepper

1/2 cup minced parsley

1/4 cup minced chives

buttered toast

Instructions:

Pour the stock into a large pot and bring to a boil over medium heat. Add the clams and cover. Cook until JUST open, about 8 minutes. Remove the clams and strain the broth through a strainer lined with cheesecloth (or a coffee filter) and reserve.

Shuck the cooked clams and coarsely chop them. Reserve.

Heat the butter in a large, heavy pot over medium heat. Add the fennel, chile, onion, celery and carrots. When the vegetables appear glassy, after 12 to 15 minutes, add the celery seeds and fennel seed and cook for another minute. Add the potatoes and the reserve broth and bring to a simmer. Cook until the potatoes are tender, about 20 minutes.

Add the clams and heavy cream and season with salt. Reduce the heat to low and simmer very gently for about 20 minutes to thicken the cream a little. Spoon into bowls and garnish the clam chowder with minced parsley and chives. Serve with buttered toast.

I find the best way to toast celery seeds and fennel seeds is in a small, dry sauté pan set over medium heat. It should take just a couple of minutes. Be careful not to let them burn. Cool slightly, and then crush them using a mortar and pestle.